I’m about to take you on a thrilling journey to uncover the story of how the stunning Hawaiian islands were formed.

Picture this: a dream honeymoon destination, where breathtaking sunsets cast their warm glow over a tropical paradise.

But beneath this idyllic surface, lies a world of raw and untamed power, where active volcanoes unleash their fury through spectacular volcanic eruptions.

We’re diving deep into the extensive history behind these island chains, exploring the intricate processes that sculpted their stunning landscapes and made them the paradisiacal wonders they are today.

Formation of Hawaiian Islands: The Hot Spot

The formation of the Hawaiian Islands is a fascinating geological process tied to the movement of tectonic plates and the presence of a hot spot.

Imagine a giant puzzle of Earth’s outer crust, consisting of tectonic plates that are constantly in motion. In some regions around the edge of the plates, volcanoes can sprout up, shaping the landscape.

Nonetheless, the Hawaiian Islands have a unique story to tell because they were born in the middle of the Pacific Plate rather than in a plate boundary.

Unlike volcanoes formed at plate boundaries, where plates grind against each other, Hawaii’s island volcanoes popped up in the middle of a tectonic plate.

This bulge in the middle of a plate pushing through the ocean floor is called a hot spot. It’s essentially a fixed location deep within the Earth’s upper mantle where molten rock, or magma, rises towards the surface.

Now, picture the Pacific Plate slowly gliding over this stationary hot spot beneath the Pacific Ocean. As it moves, the hot spot remains constant.

This continuous movement of the Pacific Plate over the hot spot led to the formation of the Hawaiian chain of islands.

The Evolution of Hawaiian Islands

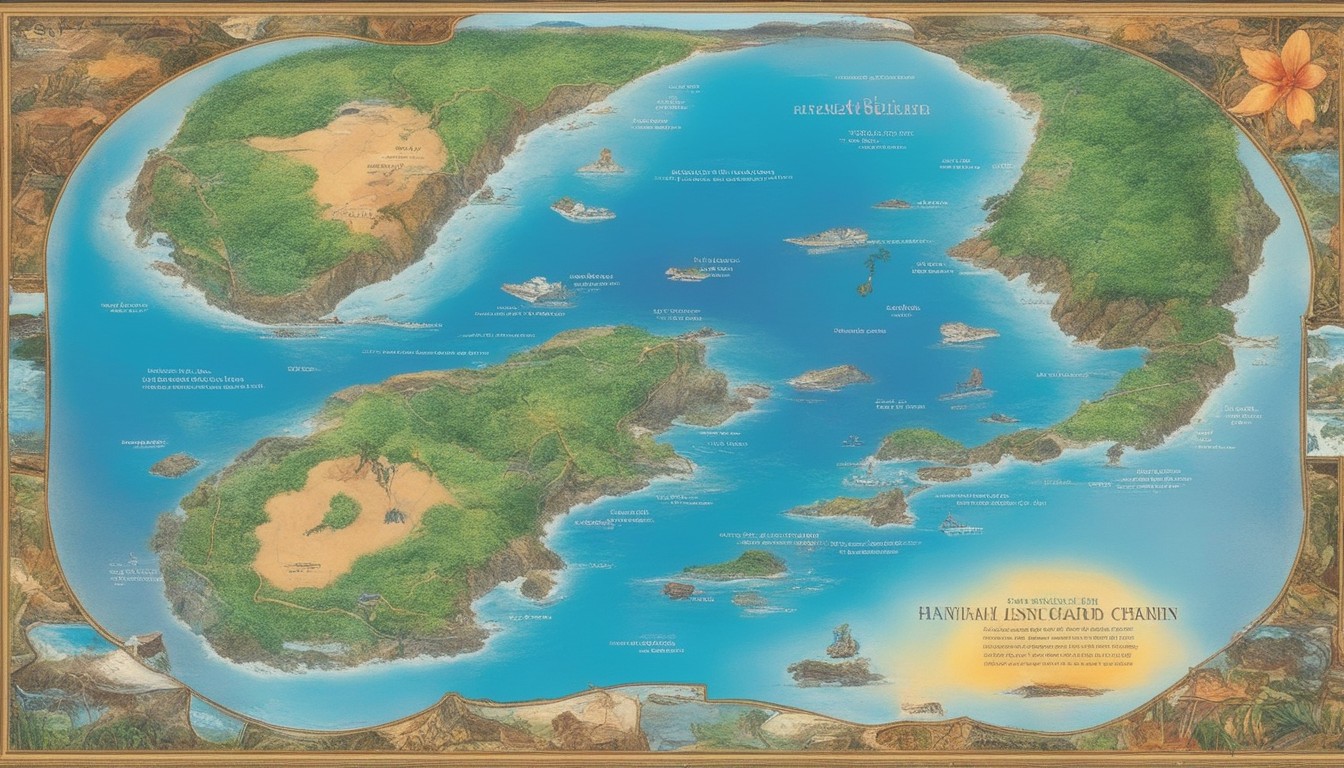

The Hawaiian Island-Emperor Seamount chain offers us a remarkable glimpse into the transformation of these volcanic islands over time. Think of it as a chronological map, with age increasing as you move away from the hot spot.

At the northernmost tip of this chain lie the Emperor Seamounts. The oldest among them, the Meiji Seamount, has been around for a staggering 80 million years and now resides near the Aleutian trench.

This age tells us that the Hawaiian hot spot has been bubbling with volcanic activity since at least the Late Cretaceous period. Fun fact: The seamount was named after the 122nd Japanese Emperor, Meiji.

Shift your focus to the southernmost end of the chain. These islands are the most recent additions, shaped by the ongoing volcanic activity of the hot spot.

Within the region sits Kīlauea volcano, and hidden beneath the ocean’s surface lies Kama’ehuakanaloa Seamount, formerly Lō’ihi Seamount. The latter is the youngest member of the Hawaiian Island chain.

Hawaiian Island Chain Life Cycle

The Hawaiian Island formation life cycle is a captivating journey through the dynamic forces of our planet’s geology. It all started from the fiery birth of undersea volcanoes to the ongoing volcanic activity that continues to shape the youngest member of the chain, Hawaii’s Big Island.

1. Submarine Preshield Stage

The submarine preshield stage is the initial phase in the life cycle of Hawaiian volcanoes, and it sets the stage for their eventual emergence as major islands.

During this phase, eruptions are relatively infrequent and produce small volumes of molten lava. These eruptions give rise to pillow lava formations, creating a steep-sided underwater volcanic structure. The result is a shallow summit caldera with typically two or three rift zones showing at the top.

What’s particularly intriguing about this stage is the formation and repeated filling of calderas, which are large volcanic craters created by the accumulation of magma beneath the surface.

The preshield stage, while lasting approximately 200,000 years, plays a relatively minor role in the overall volume of the volcano.

As the volcano steadily expands, the lava changes, causing eruptions to happen more often and become larger. It signals the transition to the shield-building stage—a pivotal phase in the development of Hawaiian islands.

Currently, the only active example of a preshield stage volcano is Kama’ehuakanaloa Seamount (formerly Lō’ihi Seamount), situated off the south coast of Hawai’i Island.

It offers valuable insights into the early stages of Hawaiian volcano formation. The geological site showcases the transition from the submarine preshield stage to the subsequent shield-building stage.

Although Kama’ehuakanaloa Seamount is the only actively observed case, experts widely believe that all Hawaiian volcanoes undergo a similar deep submarine stage.

2. Shield-Building Stage

The shield-building stage is the second critical phase in the creation of Hawaiian volcanoes. During this stage, the volcano starts as an underwater shield, formed by dense lava flows.

Beneath the ocean, as these flows erupt, the pressure from the water traps gasses like oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide within the magma, keeping them dissolved.

When the volcano gets closer to the ocean surface, these gasses begin to escape, creating bubbles in the lava, which can be seen as vesicles in the solidified rock.

When the volcano nears the ocean’s surface, the lava mixing with seawater creates steam jets, shatters rocks and turns lava into vapor.

While we don’t see such eruptions in modern Hawaii, similar events have been observed in other places like Iceland.

This stage is responsible for over 95% of a Hawaiian volcano’s total volume and can last up to 2 million years.

Currently, two well-known Hawaiian volcanoes, Mauna Loa and Kīlauea, are in the shield-building stage. Mauna Loa likely started this stage around 0.6 to 1 million years ago, while Kīlauea transitioned into it approximately 155,000 years ago.

3. Sub-Aerial Shield Building Stage

The subaerial shield-building stage is an exciting part of Hawaiian volcanoes’ journey. When the active volcanoes pop out of the ocean, the lava they spew changes, becoming more fluid.

This lava erupts with power and paints the volcano’s shape over hundreds of thousands of years, creating the classic shield shape we associate with Hawaii.

As the stage progresses, the volcanoes erupt from both the top and the sides through channels created by rift zones.

Sometimes, they erupt so vigorously that they blow the top off, forming huge craters called calderas. Not all volcanoes have these craters, though.

Two famous volcanoes in this stage are Mauna Loa and Kīlauea, which both have large calderas at the top.

4. Post-Shield Stage

The postshield stage comes near the end of the Hawaiian volcanoes’ life cycle. By this stage, the volcano adds a protective layer of lava on top.

These special cap lavas often contain components called phenocrysts, which are like early-formed crystals that get caught in the erupting lava.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. As these crystals grow, they change the composition of the remaining lava. Sometimes, this leads to eruptions of unusual lavas that are rich in silica and no longer classified as basalt.

Not all Hawaiian volcanoes follow this script. Some, like Ko‘olau on Oahu and Lāna‘i volcano, skip this postshield stage altogether.

On the other hand, you have volcanoes like Waiʻanae on O‘ahu and Mauna Kea on the Big Island that follow the postshield stage sequence.

High lava fountains shoot out, creating cinder and short, thick ‘a‘ā flows that pile up near the summit and rift-zone vents.

‘A‘ā is a Hawaiian term for lava flows characterized by a jagged, rocky surface made up of shattered lava blocks known as clinkers. These lavas often fill and overflow the caldera formed during the earlier shield-building stage.

As time goes on, the eruption rate decreases, typically over about 500,000 years, but this stage can last as long as 1 million years.

Subsequently, a phase of erosion and sinking ensues, carving deep canyons into the sides of the volcano. As the volcanic islands erode and gradually subside, fringing coral reefs begin to flourish.

East Maui’s Haleakalā Volcano began its postshield stage around 900,000 years ago. Hualālai and Mauna Kea on the Island of Hawaii are also in the postshield stage.

5. Renewed Stage

Now, begins the fourth stage, where Hawaiian volcanoes experience a rejuvenated or renewed phase of volcanism.

During this stage, which can span several million years, eruptions become relatively rare, contributing less than 1% to the volcano’s total eruptive volume. Additionally, the volcano is likely now further away from the hot spot.

Interestingly, these eruptions often occur through offshore reefs, formed from ongoing erosion.

Close to the shore, eruptions give rise to volcanic maars, while further inland, lava flows take shape along eroded stream valleys. Think of places like Mānoa Valley on O‘ahu as an example.

Here’s where things can get dramatic. Hawaiian volcanoes occasionally go through massive, cataclysmic events. During these episodes, enormous landslides tear away the vulnerable seaward sides of the islands.

These massive slides propel enormous chunks of debris across the seafloor, setting off tsunamis that can surge to incredible heights, occasionally reaching as far as 980 feet above the sea’s surface.

Kohala and Haleakalā serve as prime examples of volcanoes in this erosional stage. You’ll also find rejuvenated-stage lava features on the islands of Kaua‘i, Ni‘ihau, Moloka‘i, and West Maui.

6. Reef Growth Stage

Hawaii’s tropical location provides the perfect conditions for the formation of vibrant coral reefs.

These underwater wonders predominantly flourish on the sheltered, or leeward, side of each island, where the water remains exceptionally clear, thanks to minimal river runoff.

What’s remarkable is that many of these corals thrive right at sea level or close to it, making the reefs exceptional indicators of sea level changes over time.

Over time, as the Hawaiian islands grow older, the coral reefs gradually expand, encircling each island.

The growth process starts early, with even relatively young volcanoes like Mauna Loa hosting budding reefs. But it’s on the more mature islands, such as O’ahu and Kaua’i, where you’ll find extensive, fully developed fringing reefs that have had the time to reach their full potential.

7. Atoll Stage

In the atoll stage of Hawaiian island evolution, as volcanoes move away from the hot spot, they cool, become extinct, and sink.

Erosion, driven by waves and streams, further diminishes the islands. Fringing coral reefs expand, as the islands collapse and erode, encircling the once-mighty volcanoes.

Eventually, the structures erode to sea level, leaving behind only the circular reef, creating an atoll. Many northwestern Hawaiian Islands, like Midway Atoll, have reached this serene atoll stage.

8. Guyot Stage

In the Guyot stage, subsidence gradually submerges coral atolls beneath the sea’s surface. These once-thriving coral reefs become flat-topped seamounts, known as guyots.

The Emperor Seamounts serve as examples of this stage, marking the final chapter in the Hawaiian volcanoes’ life cycle.

Millions of years from now, these seamounts and Hawaiian islands will embark on a journey back to the Earth’s molten mantle, as they’re drawn down through subduction at an active plate boundary

Volcanic Formation and Hawaiian Culture

Long ago, the original Hawaiian inhabitants were true nature enthusiasts. Their entire worldview was a mirror of their environment.

Now, allow me to regale you with the ancient Hawaiian tale of Pele, the fiery goddess of volcanoes.

She began her journey on the islands of Kaua’i and Ni’ihau, the eldest of the eight main Hawaiian Islands. But these islands didn’t suit her fiery disposition because they were ruled by her aquatic rival, Nāmaka, the ocean goddess.

Pele embarked on a quest, island-hopping from Kaua’i to O’ahu, seeking refuge from her relentless sister. But Nāmaka’s influence was everywhere, even on O’ahu.

The journey continued, leading Pele to Moloka’i, Lāna’i, and Maui, where she hoped for respite. Alas, even the colossal Haleakalā volcano couldn’t provide sanctuary.

Finally, on Hawai’i Island and within the depths of Kīlauea, Pele dug deep with her trusty stick and unearthed a fire that Nāmaka couldn’t quench. In this youngest volcano, Pele found her permanent home.

This ancient story beautifully captures the age progression of Hawaiian volcanoes, weaving their geological history into a vibrant narrative passed down through generations.

Final Thoughts

Throughout their geological journey, Hawaiian islands go through several stages, from volcanic birth to atoll maturity.

It all starts with booming eruptions, shaping the islands’ basic form. As time passes, volcanoes drift away from the hotspot, cooling and becoming dormant. Erosion takes over, chiseling away at the islands from above, while subsidence drags them downward.

Coral reefs expand, embracing eroding landmasses. Eventually, the volcanoes erode to sea level, leaving only circular reefs, forming atolls.

This cycle, spanning millions of years, illustrates the relentless forces of nature, crafting Hawaii’s ever-changing and awe-inspiring landscapes.